Measure Sound Better

NEW

Products

Featured Products

Product Lines

Deliver reliable products for acoustic measurement and testing

Sensors

Provides measurement microphones, mouth simulators, ear simulators, and more for accurate acoustic measurements.

Data Acquisition

Combines hardware and software for high-speed, high-precision signal acquisition, ideal for various acoustic applications.

Acoustic Imaging

Offers acoustic cameras for gas leak detection, partial discharge, and fault diagnostics across handheld, fixed, and UAV platforms.

Noise Measurement

Includes sound level meters, noise sensors, and monitoring systems for effective noise measurement and analysis.

Electroacoustic Test

Delivers complete electroacoustic testing solutions, including analyzers, testing software, and acoustic test boxes.

Solutions

Provide high-quality solutions for the acoustic field

Blogs

Share insights, cases and trends in acoustic testing

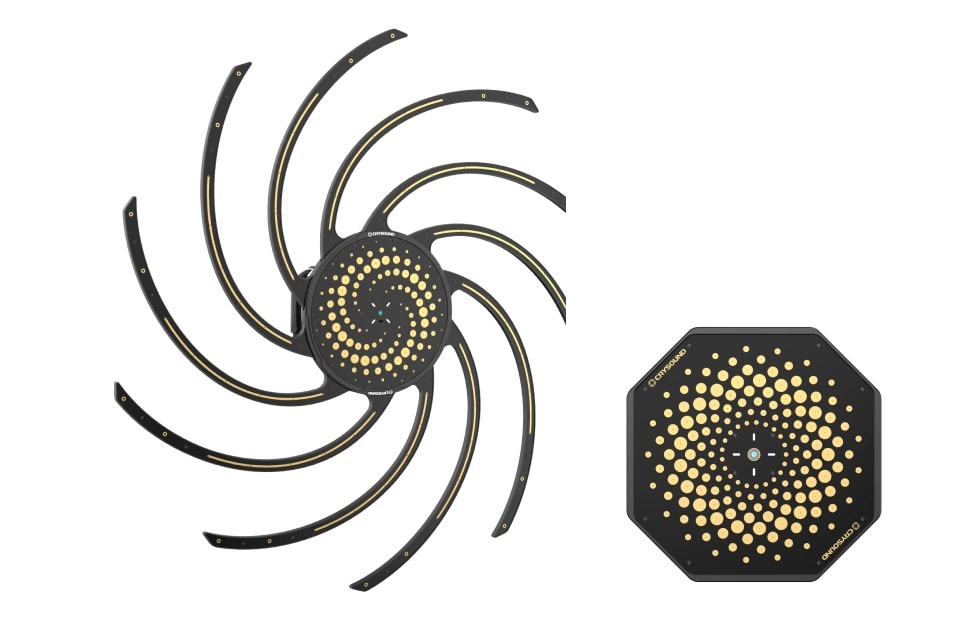

An acoustic camera is one of the most powerful tools available to engineers who need to locate, visualize, and quantify noise sources in complex environments. Whether you are troubleshooting an unwanted rattle inside a vehicle cabin, tracking down air leaks in a compressed-air system, or verifying the acoustic performance of a home appliance on the production line, an acoustic camera can do in minutes what traditional measurement methods take hours—or fail to do at all. This complete guide explains how acoustic cameras work, where they are used, what to look for when choosing one, and how they compare to conventional sound level meters. By the end, you will have a clear understanding of sound source localization technology and the confidence to select the right acoustic imaging camera for your application. What Is an Acoustic Camera? An acoustic camera is an instrument that combines a microphone array with a digital camera to produce a real-time visual map of sound—often called an acoustic image or sound map. The colored overlay shows exactly where noise is coming from, its relative intensity, and how it changes over time or frequency. Unlike a single microphone, which can measure sound pressure at one point but cannot tell you where the sound originates, an acoustic camera performs noise source identification across a wide field of view simultaneously. Core Components Component Role Microphone array Captures sound at multiple spatial positions Digital camera Provides the optical reference image Data acquisition hardware Digitizes and synchronizes all microphone channels Beamforming software Computes the sound map from array data How Does an Acoustic Camera Work? The Beamforming Principle The physics behind an acoustic camera relies on a technique called beamforming. Here is a simplified explanation: Sound waves arrive at the microphone array. Because microphones are at different positions, the same wavefront reaches each microphone at a slightly different time. Time delays are calculated. For every candidate point in the measurement space, the software calculates the expected arrival-time differences across all microphones. Signals are shifted and summed. The software shifts each microphone signal by the predicted delay and sums them. If the candidate point is the true source, the signals add constructively, producing a strong peak. If not, they partially cancel. A sound map is generated. By scanning thousands of candidate points, the algorithm builds a 2D (or 3D) color map of acoustic intensity overlaid on the camera image. This process is called delay-and-sum beamforming and is the foundation of most acoustic cameras. More advanced algorithms—such as CLEAN-SC, functional beamforming, and deconvolution approaches—further sharpen the image and improve dynamic range. Frequency Range and Array Design The usable frequency range of an acoustic camera depends on the array geometry: Low-frequency limit is governed by the overall array diameter. A larger array resolves lower frequencies. High-frequency limit is governed by the spacing between adjacent microphones. Closer spacing avoids spatial aliasing at higher frequencies. Typical acoustic cameras cover 200 Hz to 12 kHz or wider, with some specialized arrays reaching above 20 kHz for applications like leak detection. Applications of Acoustic Cameras Automotive NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) Acoustic cameras are indispensable in automotive development. Engineers use them to: Identify wind noise sources around door seals, mirrors, and A-pillars in wind-tunnel tests. Locate interior noise paths—dashboard rattles, HVAC duct noise, powertrain radiation—during road tests. Validate pass-by noise levels under ISO 362 by mapping exterior noise sources in real time. Home Appliance Noise Reduction Consumer expectations for quiet appliances are rising. Manufacturers of washing machines, refrigerators, dishwashers, and air conditioners use acoustic cameras to: Compare noise signatures before and after design changes. Detect abnormal noise patterns in end-of-line (EOL) quality checks. Pinpoint noise from specific subcomponents (compressors, fans, pumps) within a fully assembled product. Industrial Equipment and Predictive Maintenance In factories, acoustic cameras quickly identify: Compressed-air leaks, which account for 20–30% of energy waste in many plants. Bearing defects in motors, turbines, and conveyors—often before they become audible to the human ear. Electrical discharge (partial discharge) in high-voltage switchgear and transformers. Building Acoustics and Environmental Noise Acoustic cameras help building consultants identify sound transmission paths through walls, windows, and HVAC penetrations, verify the effectiveness of sound barriers, and map noise from construction sites. Power Generation and Renewable Energy Wind turbine manufacturers and operators use acoustic cameras to measure blade noise, detect trailing-edge damage, and comply with environmental noise limits. How to Choose an Acoustic Camera 1. Array Configuration and Size Planar arrays (flat) are the most common—lightweight, portable, and suitable for front-facing measurements. Spherical or 3D arrays capture sound from all directions for interior cabin or room acoustic studies. Number of microphones: More microphones improve spatial resolution and dynamic range. Entry-level: 30–64; high-performance: 100–200+. 2. Frequency Range Application Typical Frequency Range Automotive NVH (interior) 200 Hz – 8 kHz Appliance noise 300 Hz – 12 kHz Air leak detection 2 kHz – 20 kHz+ Building acoustics 100 Hz – 5 kHz 3. Software Capabilities Real-time beamforming, advanced algorithms (CLEAN-SC, deconvolution), time-domain and frequency-domain analysis, video recording with synchronized audio, and flexible export formats. 4. Portability and Ease of Use For field measurements, a lightweight, battery-powered, single-person-operable system is essential. A Closer Look: CRYSOUND Acoustic Imaging Systems The CRY8124 is a large-format planar array with 200 MEMS microphones, optimized for high-resolution measurements in automotive NVH and industrial applications. The CRY2623 is a compact, handheld acoustic camera with 128 microphones designed for rapid field inspections—air leak detection, electrical inspection, and predictive maintenance. Both systems include real-time beamforming software with CLEAN-SC deconvolution, video overlay, and spectral analysis. Acoustic Camera vs. Sound Level Meter: When to Use Which Criterion Sound Level Meter Acoustic Camera What it measures Sound pressure level at one point Sound source location and relative level across a surface Source identification No Yes—visual map shows source locations Regulatory compliance Yes—traceable dB(A)/dB(C) values per IEC 61672 Limited Cost $500–$5,000 $15,000–$150,000+ Best for SPL measurement, noise monitoring, compliance Root-cause analysis, noise reduction, leak detection In practice, the two tools are complementary. A sound level meter confirms how loud a problem is; an acoustic camera shows where it is. Conclusion Acoustic cameras have transformed the way engineers approach noise problems. By making sound visible, they accelerate root-cause analysis, reduce development cycles, and enable quality controls that were previously impractical. Ready to see your noise sources? Contact CRYSOUND for a personalized consultation or request a live demo with your application.

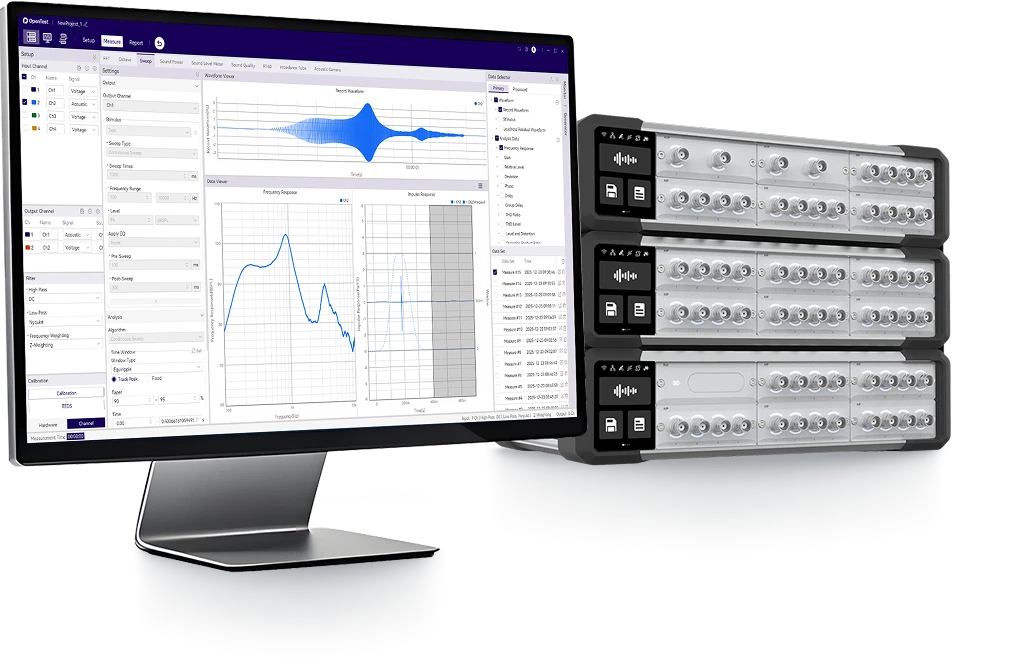

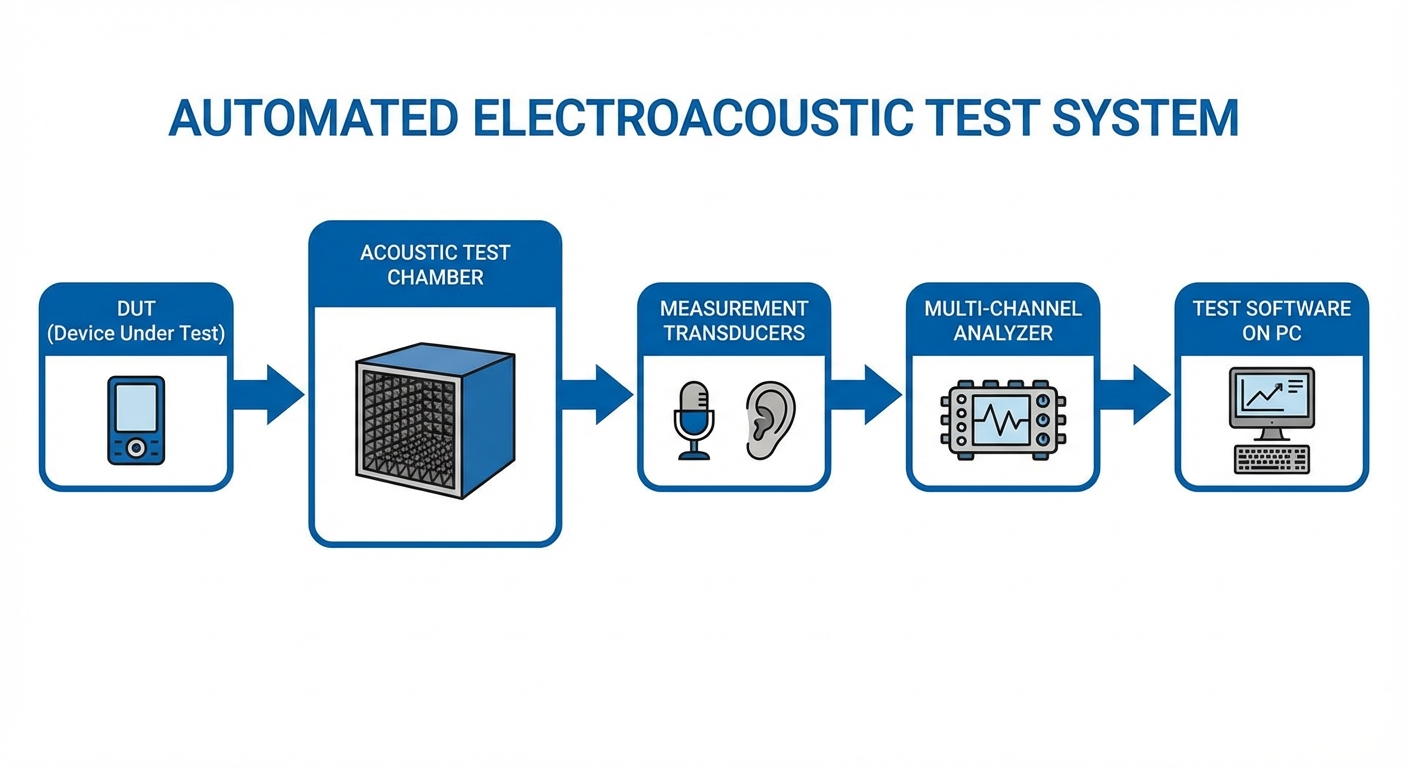

Every speaker, microphone, headphone, and hearing aid that leaves a production line must meet precise acoustic specifications. This guide walks you through the transition from manual electroacoustic testing to a fully automated audio test system. Why Automate? Manual Testing vs. Automated Testing The Manual Approach A typical manual setup consists of a signal generator, power amplifier, measurement microphone, audio analyzer, and an operator who connects the DUT, triggers each measurement, reads results, and records pass/fail. Limitations: Slow (2–5 min/unit), operator-dependent, error-prone, difficult to scale. The Automated Approach Factor Manual Automated Test time per unit 2–5 minutes 5–15 seconds Throughput 15–25 units/hour 200–500+ units/hour Repeatability Operator-dependent < 0.5 dB variation Data logging Manual/partial Automatic, 100% traceability Defect detection Subjective Algorithmic, consistent ROI is typically realized within 6–12 months for mid-volume production (>500 units/day). System Architecture: Hardware and Software 1. Signal Generation and Acquisition (Audio Analyzer) Modern audio analyzers integrate signal generation and acquisition in a single instrument with USB or Ethernet connectivity. 2. Acoustic Test Chamber (Test Fixture) The DUT must be tested in a controlled acoustic environment—anechoic coupler, semi-anechoic test chamber, or IEC 60318-compliant ear simulator. 3. Switching and Connectivity Relay matrix, barcode/QR scanner, PLC or I/O controller for conveyor systems and MES integration. 4. Test Software CRYSOUND's OpenTest platform provides a drag-and-drop test sequence editor, multi-station deployment, and built-in SPC dashboards. Key Electroacoustic Test Parameters Frequency Response: SPL vs. frequency curve evaluated against upper and lower limit masks Total Harmonic Distortion (THD): < 1% at 1 kHz rated power typical spec Rub and Buzz (R&B): Detects mechanical defects—loose particles, voice coil rub, rattling Impedance: Reveals resonant frequency, DC resistance, electrical behavior Polarity: Verifies correct phase direction Sensitivity: SPL at reference distance for given input Seal and Leak Test: For enclosed products Step-by-Step: Building Your Automated Test Line Define Test Requirements — List every parameter, pass/fail limits, cycle time, and applicable standards. Design the Test Station Layout — Calculate station count, inline vs. offline, one-sided vs. multi-sided. Select and Procure Equipment — Audio analyzer, microphones, test chamber, switching hardware, software. Build and Integrate — Assemble fixtures, wire signal paths, install software, connect PLC/MES. Establish Golden Unit Calibration — Select 5–10 reference units, define reference curves and repeatability baseline. Validate and Fine-Tune Limits — Run pilot batch of 100–500 units, analyze yield, adjust thresholds. Train Operators and Launch — Document procedures, go live with full data logging. Continuous Improvement — Daily calibration verification, SPC monitoring, periodic microphone recalibration. Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them Inadequate Acoustic Isolation: Design chamber for ≥30 dB insertion loss. Over-Tight Limits at Launch: Use pilot-batch statistics (mean ± 3σ). Ignoring Fixture Repeatability: Use positive-location fixtures, verify with gauge R&R. No Reference Unit Tracking: Measure reference unit at start of each shift. Conclusion Transitioning from manual to automated electroacoustic testing pays for itself through higher throughput, better repeatability, and comprehensive data traceability. The acoustic quality your customers hear is only as good as the test system that verified it. Ready to automate your electroacoustic test line? Contact CRYSOUND to discuss your production testing requirements. From audio analyzers and measurement microphones to the OpenTest software platform, CRYSOUND provides end-to-end solutions for production line audio testing.

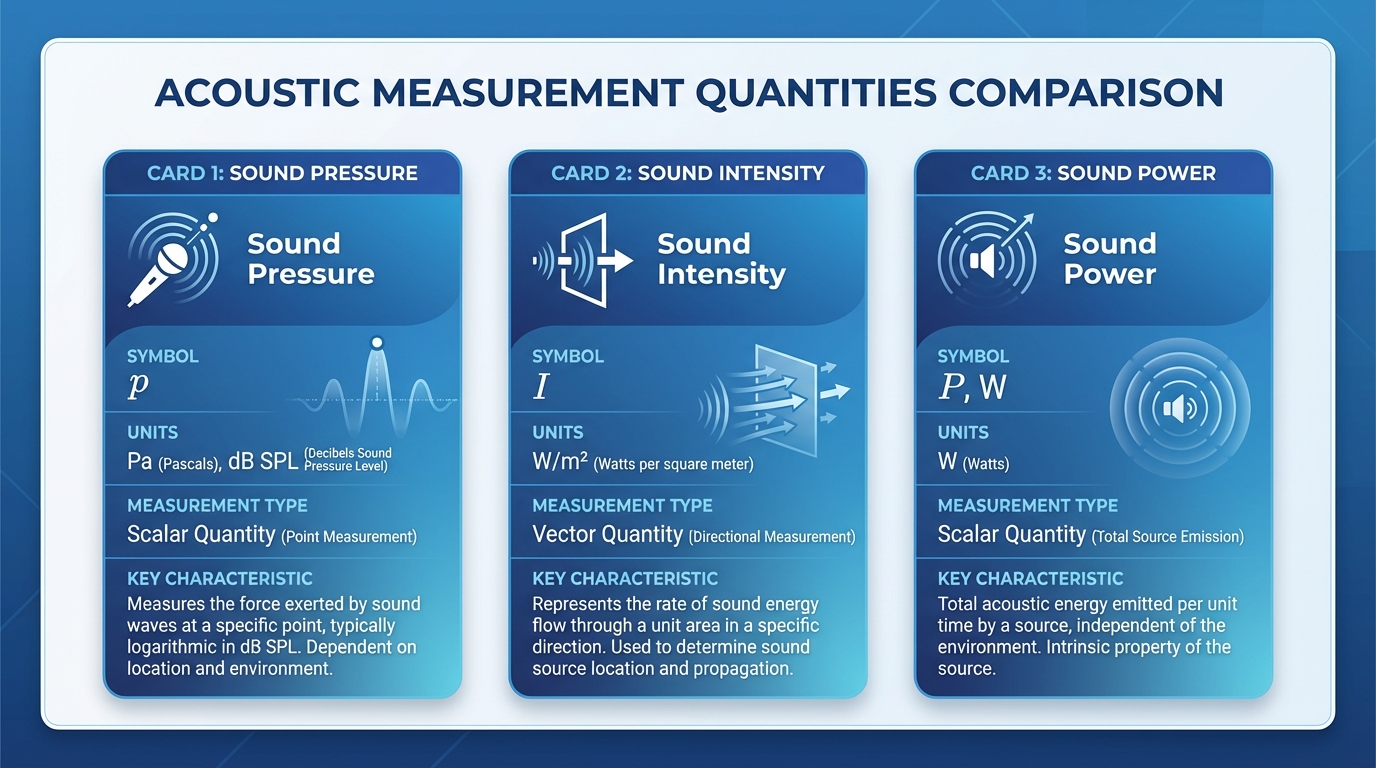

Sound pressure level, sound intensity, and sound power are three fundamental quantities in acoustic measurement, yet they are routinely confused—even by experienced engineers. This guide explains what each quantity physically represents, how they relate to each other, how to measure them according to international standards, and—most importantly—when to use which one in real engineering practice. The Three Quantities at a Glance Quantity Symbol Unit What It Describes Depends on Environment? Sound Pressure p (level: Lp) Pa (dB re 20 µPa) Force per unit area at a point Yes Sound Intensity I (level: LI) W/m² (dB re 1 pW/m²) Energy flow per unit area in a direction Partially Sound Power W (level: LW) W (dB re 1 pW) Total acoustic energy radiated by a source No The key distinction: sound pressure and intensity depend on where you measure; sound power is an intrinsic property of the source. Sound Pressure: What You Hear Sound pressure is the local fluctuation in air pressure caused by a sound wave. Sound pressure level (SPL) is expressed as: Lp = 20 × log₁₀(p / p₀) where p₀ = 20 µPa is the reference pressure. Key characteristics: Scalar quantity, location-dependent, easy to measure with a single calibrated microphone. When to use: Noise exposure assessment (ISO 9612), environmental noise monitoring, product noise labeling, quick field checks. Sound Intensity: Energy Flow with Direction Sound intensity is the rate of acoustic energy flow through a unit area in a specified direction—a vector quantity with both magnitude and direction. Key characteristics: Directional, less sensitive to background noise, requires specialized two-microphone probe. When to use: Sound power determination in situ (ISO 9614), noise path identification, transmission loss testing. Sound Power: The Source’s Intrinsic Noise Rating Sound power is the total acoustic energy radiated by a source per unit time—independent of environment. When to use: Product noise specifications (EU Machinery Directive), noise prediction and modeling, procurement and tendering. Measurement Methods and ISO Standards Sound Power via Sound Pressure (ISO 3741–3747) Standard Environment Accuracy ISO 3741 Reverberation room Precision (Grade 1) ISO 3744 Free field over reflecting plane Engineering (Grade 2) ISO 3745 Anechoic / hemi-anechoic room Precision (Grade 1) ISO 3746 In situ (any environment) Survey (Grade 3) Sound Power via Sound Intensity (ISO 9614 series) The advantage of the intensity method is its tolerance of background noise and reflections. Measurement Equipment CRYSOUND’s multi-channel data acquisition range includes prepolarized and externally polarized models in 1/2-inch and 1/4-inch formats, covering frequency ranges from 3 Hz to over 100 kHz. CRYSOUND’s data acquisition platforms support intensity measurement with real-time cross-spectral analysis across all channels. Practical Decision Guide: Which Quantity Do You Need? “I need to check workplace noise regulations.” → Measure sound pressure level per ISO 9612. “I need to compare noise output of two machines.” → Request or measure sound power level. “I need to find where noise leaks through a wall.” → Measure sound intensity on the receiving side. “I need to predict how loud a new machine will be.” → Get the machine’s sound power level, then model. “I need to meet the EU Machinery Directive.” → Determine sound power level per ISO 3744/3746. Summary Table Sound Pressure Level Sound Intensity Level Sound Power Level Quantity type Scalar Vector Scalar Depends on distance Yes Yes No Depends on room Yes Partially No Primary instrument Sound level meter Intensity probe Calculated from SPL or intensity Key standards IEC 61672 ISO 9614 ISO 3741–3747 Best for Exposure, compliance Path analysis, in-situ power Source comparison, prediction Conclusion Sound pressure tells you how loud it is here. Sound intensity tells you how much energy is flowing that way. Sound power tells you how much noise the source makes, period. By understanding these distinctions and selecting the right measurement method, you avoid costly errors and arrive at actionable acoustic data faster. Need help selecting the right acoustic measurement equipment? Contact CRYSOUND to discuss your application with our acoustics team.

During pilot production and production line ramp-up, many issues do not appear in the way teams initially expect. Sometimes it starts with a small fluctuation at a test station, or a comment from a line engineer saying, "This result looks a bit unusual."However, when takt time, yield targets, and delivery milestones are all under pressure, these seemingly minor anomalies can quickly be amplified and begin to affect the overall production rhythm. We have been working with Huaqin as a long-term partner. As projects progressed, the challenges encountered on the production line became increasingly complex. On site, our role gradually extended from basic production test support to problem analysis and cross-team coordination during pilot production. In many cases, the focus was not simply on whether a test station was functioning, but on how to absorb uncertainties early and prevent them from disrupting delivery schedules. The following two experiences both took place during the pilot production phase of Huaqin projects. They are not exceptional cases. On the contrary, they represent the kind of everyday issues that most accurately reflect the realities of production line delivery. Airtightness Testing Issues in Project α During the pilot ramp-up of Project α, the airtightness test station for the audio microphone showed clear instability. For the same batch of products, pass rates fluctuated noticeably across repeated tests, frequently interrupting the station's operating rhythm. Initial troubleshooting naturally focused on the test system itself, including software logic, equipment status, and basic parameter settings. It soon became clear, however, that the issue did not originate from these areas. As on-site verification continued, we gradually confirmed that the anomaly was more closely related to the product's mechanical structure and material characteristics. This model used a relatively uncommon combination of materials. A sealing solution that had worked well in previous projects could not maintain consistency during actual compression. Even slight variations in applied pressure were enough to influence test results. Once the direction of the problem was clarified, the on-site approach shifted accordingly. Rather than repeatedly adjusting the existing solution, we returned to verifying the compatibility between materials and structure. Over the following period, we worked together with the customer's engineering team on the production line, testing multiple material options. This included different types of silicone and cushioning materials, variations in silicone hardness, and adjustments to plug compression methods. Each step was evaluated based on real test results before moving forward. The process was not fast, nor was it particularly clever. In essence, it came down to repeatedly confirming one question: could this solution run stably under real production line conditions?Ultimately, by introducing a customized soft silicone gasket and making fine parameter adjustments, the airtightness test results gradually stabilized. The station was able to run continuously, and the pilot production rhythm was restored. Figure 1. Test Fixture Diagram Noise Floor Issues in Project β Compared with the airtightness issue in Project α, the noise floor anomaly encountered during pilot production in Project β was more complex to diagnose. During headphone pilot production for Project β at Huaqin's Nanchang site, the noise floor test station repeatedly triggered alarms. Test data showed that measured noise levels consistently exceeded specification limits, significantly impacting the pilot production schedule. This model used high-sensitivity drivers along with a new circuit design, making the potential noise sources inherently more complex. It was not a problem that could be resolved by simply adjusting a single parameter. Rather than focusing solely on the test station, we worked with the customer's audio team to investigate the issue from a system-level signal chain perspective. The process involved sequentially testing different shielding cables, adjusting grounding strategies, evaluating various Bluetooth dongle connection methods, and isolating potential power supply and electromagnetic interference sources within the test environment. Through continuous spectrum analysis and comparative testing, the scope of the issue was gradually narrowed. It was ultimately confirmed that the elevated noise floor was primarily related to power interference from the Bluetooth dongle, combined with differences in product behavior across operating states. After this conclusion was reached, relevant configurations were adjusted and validated on site. As a result, noise floor measurements returned to a stable and controllable range, allowing pilot production to proceed. Figure 2. Work with the customer engineer to solve problems Common Characteristics of Pilot Production Issues Looking back at these two pilot production experiences, it becomes clear that despite their different manifestations, the underlying diagnostic processes were quite similar. Whether dealing with airtightness instability or excessive noise, the root cause could not be isolated to a single module. Effective resolution required on-site evaluation across mechanical structure, materials, system operating states, and test conditions. During pilot production, issues of this nature rarely come with ready-made answers. They are also unlikely to be resolved through a single verification cycle. More often, progress is made through repeated trials, comparisons, and eliminations, gradually converging on a solution that is genuinely suitable for long-term production line operation. Production line delivery rarely follows a perfectly smooth path. In many cases, what ultimately determines whether a project can move forward as planned are those unexpected issues that must be addressed immediately when they arise. In our long-term collaboration with customers, our work often takes place at these critical moments—working alongside engineering teams to stabilize processes, maintain momentum, and keep projects moving forward step by step. If you also want CRYSOUND to support your production line, you can fill out the Get in Touch form below.